The 1950's has been referred to as "The Golden Age of Cycling." By the fifties America was strictly a car culture, having reinvented the bicycle as a toy for children. But in Britain the bicycle reigned supreme. Dave Moulton, who was living in England at the time, describes in his blog the ubiquitous bike culture: "I rode my bike to work each day; a distance of five miles. My father did the same; a bicycle was his only form of transport. He never in his lifetime owned a car...

...The majority of (working class) workers arrived by public transport, bike, or on foot. Just inside the factory gates were hundreds of bike racks...No one locked their bikes; we just parked them and walked to our workplace. I wore my regular work clothes, with a water-proof cape if it rained...This was the norm for most of the working class in the UK throughout the 1950's. Cycle racing, and in particular time-trialing was very much a working class sport. Many riders had only one bike that they raced on, trained on, and was their transport to and from work."

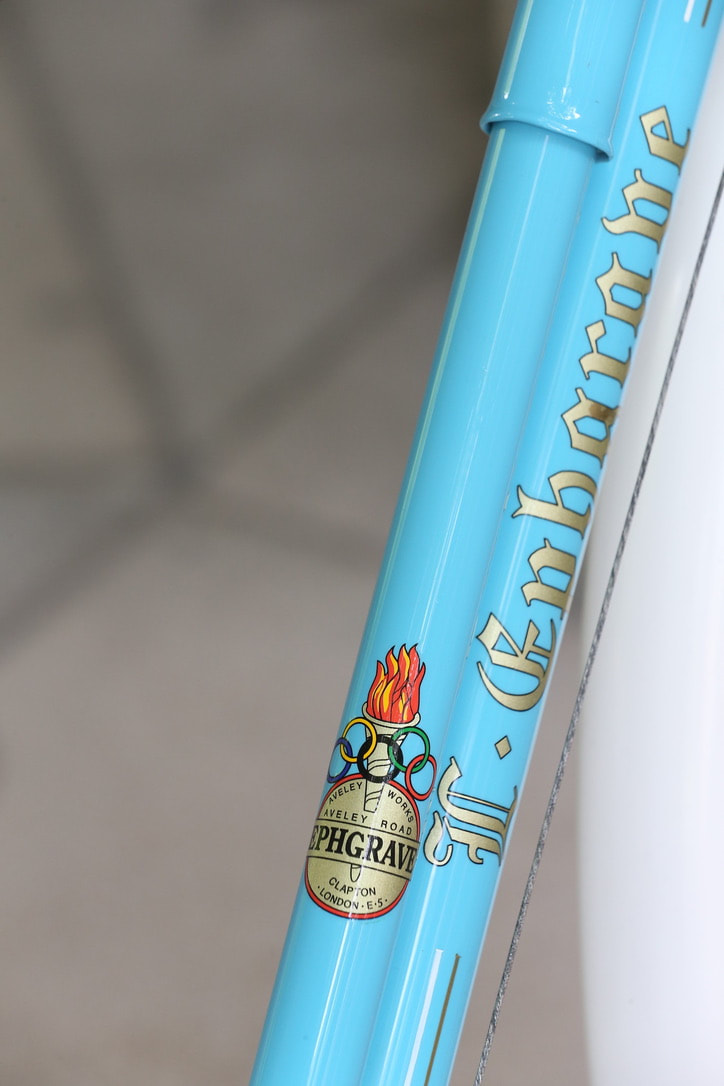

Bicycles were also a major form of recreation. Bicycle clubs such as The Cyclists Touring Club were hugely popular in Britain during the golden age. Special excursion trains were modified to accommodate bikes, allowing cyclists to escape the confines of the city and seek companionship and adventure in the countryside. Bikes were neatly stored on hooks inside a "bicycle carriage" as the train carried cyclists from the London area to the country delights of touring, sight-seeing stops, and beer. Enter the custom frame builders of the UK. Some of the most beautiful bikes ever made were created in the forties and fifties by dozens of individual craftsmen. Les Ephgrave is considered one of the masters of the post war era. Ephgrave, known as "Lou" to his friends, learned his craft working for Harry Rensch and Claud Butler, going solo in 1948. It is said that Les cut all of the Ephgrave set lugs himself. He built his last frame circa 1968.

The 1953 Ephgrave No. 1 you see here had been languishing on a hook in my cabin for many years, looking tired and worn, when I met a contemporary master frame builder, Jeffrey Bock of Ames, Iowa. Jeff agreed to restore my Ephgrave to its former glory. Over a period of several months I slowly but surely sourced the period-correct components; but this is the full extent of my contribution to the work of art you see before you. The frame repair, the build, and the flawlessly beautiful paint are all the work of Jeff Bock. (Jeff recorded his meticulous attention to detail on his Facebook page). Once the restoration was completed, Jeff asked me if I was going to ride the Ephgrave. I told him yes, but I will have to "get up my nerve." Bicycles are made to be ridden, but it isn't easy--at least for me--to take a show bike like the Ephgrave for its maiden voyage. After the inevitable first scratch, one can slowly relax and "enjoy the ride.”

“Before” photos of Ephgrave by Jeff Bock. Thanks to Christopher Maharry for photos of the Ephgrave as she is today.

...The majority of (working class) workers arrived by public transport, bike, or on foot. Just inside the factory gates were hundreds of bike racks...No one locked their bikes; we just parked them and walked to our workplace. I wore my regular work clothes, with a water-proof cape if it rained...This was the norm for most of the working class in the UK throughout the 1950's. Cycle racing, and in particular time-trialing was very much a working class sport. Many riders had only one bike that they raced on, trained on, and was their transport to and from work."

Bicycles were also a major form of recreation. Bicycle clubs such as The Cyclists Touring Club were hugely popular in Britain during the golden age. Special excursion trains were modified to accommodate bikes, allowing cyclists to escape the confines of the city and seek companionship and adventure in the countryside. Bikes were neatly stored on hooks inside a "bicycle carriage" as the train carried cyclists from the London area to the country delights of touring, sight-seeing stops, and beer. Enter the custom frame builders of the UK. Some of the most beautiful bikes ever made were created in the forties and fifties by dozens of individual craftsmen. Les Ephgrave is considered one of the masters of the post war era. Ephgrave, known as "Lou" to his friends, learned his craft working for Harry Rensch and Claud Butler, going solo in 1948. It is said that Les cut all of the Ephgrave set lugs himself. He built his last frame circa 1968.

The 1953 Ephgrave No. 1 you see here had been languishing on a hook in my cabin for many years, looking tired and worn, when I met a contemporary master frame builder, Jeffrey Bock of Ames, Iowa. Jeff agreed to restore my Ephgrave to its former glory. Over a period of several months I slowly but surely sourced the period-correct components; but this is the full extent of my contribution to the work of art you see before you. The frame repair, the build, and the flawlessly beautiful paint are all the work of Jeff Bock. (Jeff recorded his meticulous attention to detail on his Facebook page). Once the restoration was completed, Jeff asked me if I was going to ride the Ephgrave. I told him yes, but I will have to "get up my nerve." Bicycles are made to be ridden, but it isn't easy--at least for me--to take a show bike like the Ephgrave for its maiden voyage. After the inevitable first scratch, one can slowly relax and "enjoy the ride.”

“Before” photos of Ephgrave by Jeff Bock. Thanks to Christopher Maharry for photos of the Ephgrave as she is today.

After Photos

Before and During Restoration Photos

Ephgrave No. 1 ©Daniel Dahlquist